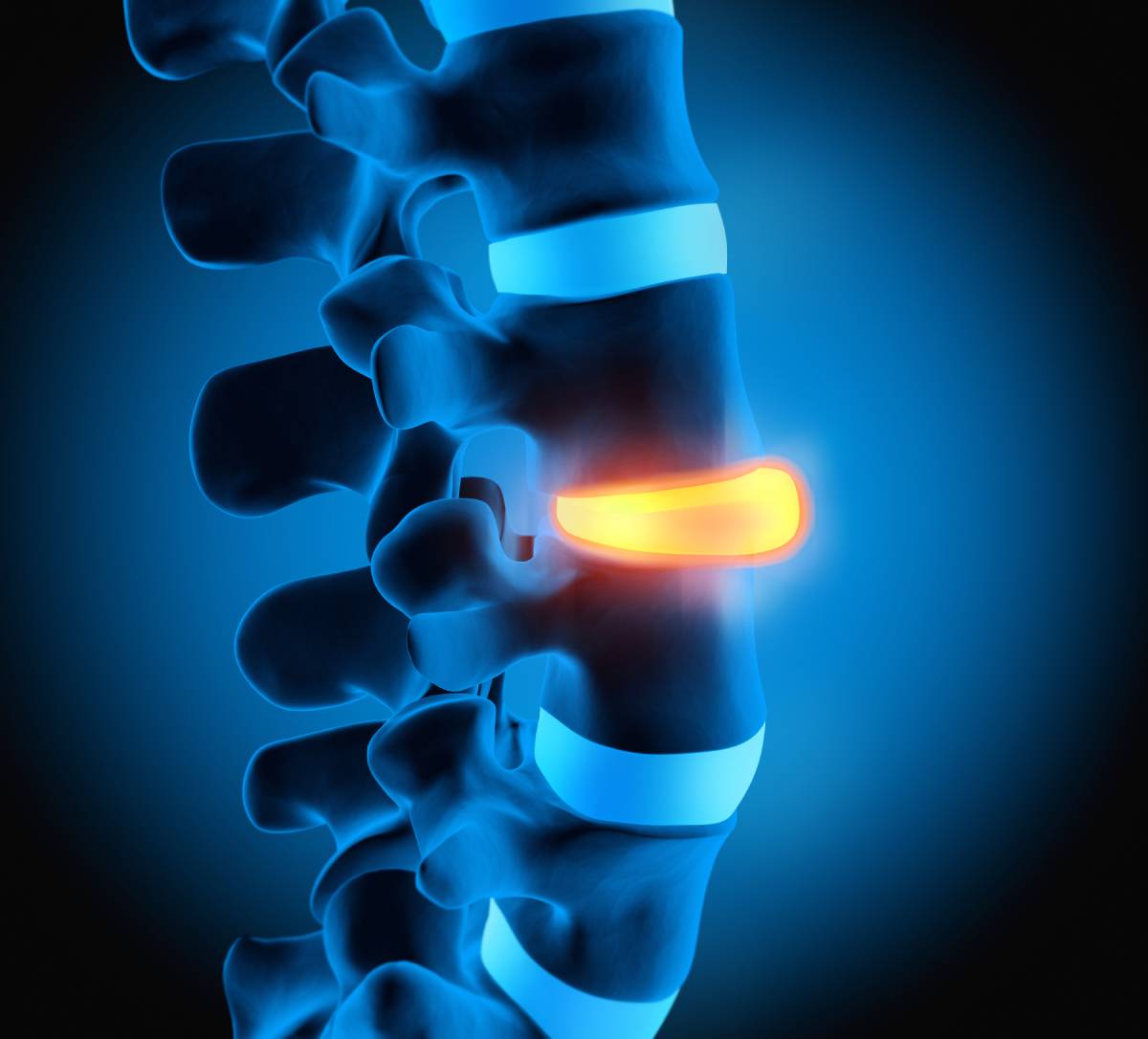

Musculoskeletal pain is a leading cause of disability 1 for which chiropractic care is key to alleviating 2–4. Since 1897, when American chiropractor B. J. Palmer’s work led to the establishment of the chiropractic profession (literally meaning, “done by hand”), chiropractic practice has reached a global scale 5. Chiropractic practice has indeed grown steadily as a discipline over the last few decades, and chiropractors now operate in approximately 100 different countries 6 – with varying degrees of accessibility and practice guidelines.

Chiropractic management includes, but is not limited to, rehabilitation exercises, joint and soft-tissue manual manipulations, and patient education. Over half of patients seek out chiropractors for back pain, while the rest tend to seek treatment for other musculoskeletal pain, arthritic pain, and headaches, including migraines. Up to one tenth of patients present with an array of symptoms exacerbated by a neuromusculoskeletal disorder.

Most chiropractors work within the first countries to have established chiropractic schools, i.e. the U.S. (75,000), Canada (7,000+), Australia (4,000+), and the United Kingdom (3,000+). However, despite their strong global presence, chiropractic professionals (and related professionals) remain under-represented in low- and middle-income countries as regards service provision, educational institutions, and legislative and regulatory frameworks 6. In Zimbabwe, Malawi, and Zambia, for example, nearly three quarters of disabled patients have an unmet need for medical rehabilitation.

To date, nearly 50 different countries have established some degree of legislation to recognize, license, and regulate the profession, usually at the national level, but sometimes at the discretion of individual states or regions, such as in the case of the U.S. Legislation may be in the form of a separate chiropractic act, a chiropractic act under an umbrella health care policy, or a chiropractic act under an umbrella complementary and alternative health care policy. Legislation does not generally require that a patient obtain a prior medical referral to consult a practitioner, and varies across countries as regards chiropractors’ rights to perform or order diagnostic tests, such as spinal imaging and laboratory tests 7.

The educational standards of the U.S. Council on Chiropractic Education have been incorporated into the World Health Organization’s Guidelines on Basic Training and Safety in Chiropractic (2005). Interestingly, across the different chiropractic programs which now span 16 countries, most are within private colleges in the U.S., while most non-American schools are newer and embedded within the national university system 7.

The past decade has been met with dynamic chiropractic research as a result of the rising number of chiropractic trainees and new public research funding. Partly as a result of this, chiropractic and other medical professions have reached unprecedented levels of collaboration in research and the development of clinical practice guidelines, primarily anchored in an overlapping approach to preventive medicine as it relates to spinal ailments.

Chiropractic services today, however, continue to face a number of challenges. Not only is there little funding for education and research, but costs often remain hefty for patients, either because chiropractic services are not included in health insurance plans, or because these are linked to very strict co-payment plans. Furthermore, the input of chiropractic professionals on policy remains meagre. Alongside further research in support of the profession, representation in policy decision-making may provide the necessary foundation for the seamless integration of chiropractic services into a balanced, end-to-end approach to patient care.

Rehabilitation by chiropractors plays a critical role in minimizing the impact of musculoskeletal conditions and chronic disability. Overall, the chiropractic profession has seen rapid growth on a global scale, while is likely to persist provided sufficient research, funding, and pro-chiropractic practice policies.

References

1. Hoy, D. et al. The global burden of low back pain: Estimates from the Global Burden of Disease 2010 study. Ann. Rheum. Dis. (2014). doi:10.1136/annrheumdis-2013-204428

2. Garner, M. J. et al. Chiropractic Care of Musculoskeletal Disorders in a Unique Population Within Canadian Community Health Centers. J. Manipulative Physiol. Ther. (2007). doi:10.1016/j.jmpt.2007.01.009

3. Dougherty, P. & Lawrence, D. Chiropractic management of musculoskeletal pain in the multiple sclerosis patient. Clin. Chiropr. (2005). doi:10.1016/j.clch.2005.03.004

4. Hawk, C. et al. Best practices for chiropractic management of patients with chronic musculoskeletal pain: A clinical practice guideline. J. Altern. Complement. Med. (2020). doi:10.1089/acm.2020.0181

5. Sportelli, L. The discovery, development and current status of the chiropractic profession. Integr. Med. (2019).

6. Stochkendahl, M. J. et al. The chiropractic workforce: A global review. Chiropractic and Manual Therapies (2019). doi:10.1186/s12998-019-0255-x

7. The Current Status of the Chiropractic Profession Report to the World Health Organization from the World Federation of Chiropractic. (2012).